While Japan has weathered the COVID-19 storm better than most, new data shows Japan’s infectious diseases research effort has been lagging behind for years, drawing criticism from the country’s researchers.

“We are standing on the brink of a global crisis in infectious diseases. No country is safe from them. No country can any longer afford to ignore their threat.”

Dr Hiroshi Nakajima (1928–2013) Former Director-General of WHO (1996)

These prophetic words from the late Dr Hiroshi Nakajima headlined the release of the World Health Organization’s World Health Report 1996, warning of “fatal complacency among the international community” and urging preventative action in the face of impending crises for the globe. Just one generation later, all nations globally have been subjected to a one-in-100-year pandemic that has so far killed more than 6.6 million people and infected more than 650 million.

One wonders what Dr Nakajima would say of his home country, Japan, which has fared better during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with most nations, with 52,000 dead among more than 26 million cases (source: Johns Hopkins University). But new data and the voices of key researchers suggest Japan has been ignoring Dr Nakajima’s warning – and the threat – for too long, by not investing enough in infectious diseases research, despite Japan’s economic status and various strengths in research and innovation.

This exclusive analysis – using data from the Dimensions database of 130 million publications and journals included in the Nature Index – builds a picture of how infectious diseases research in Japan has stalled over the last few decades, and in particular in the years leading up to and including the start of the pandemic. It’s data that comes as no surprise to some of Japan’s leading researchers in the field.

“Cancer is king”

Concerns about the level of Japanese government funding for infectious diseases research have been held by scientists in Japan’s top universities, hospitals and research centres for years.

“Cancer is king, and the genome is queen. Infectious disease is just a pathogen,” quips Professor Makoto Suematsu, Dean of the School of Medicine at Keio University, one of Japan’s research hospital universities. Professor Suematsu, who is keenly interested in biology and public health, describes funding in Japan for infectious diseases research as being “very weak” and “very minor”, the majority of which goes to the government-controlled National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID) – with not enough to share around.

Exactly why “cancer is king” is a matter of demography. “The Japanese are suffering from an ageing population, so the budget has increased for taking care of old people. The budget for the elderly is huge – imagine it is a watermelon and one seed is the budget for infectious diseases research. But it [ageing] is a big problem – two-thirds of the Japanese population will be over 60 in 2040,” Professor Suematsu says.

He says funding is also hampered by regulations within Japan and a lack of private investment: “Unlike in the UK, there is no Wellcome Trust or similar bodies.

“Only prestigious institutions get funding from the government, so Tokyo University for example gets lots of funding. Keio and other private universities get limited government support so it’s quite tough for staff supporting COVID research.”

His comments are echoed by Dr Norio Ohmagari, Director of Disease Control and Prevention at Japan’s National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM). He also is not surprised to learn that the data shows Japan lagging behind on infectious diseases research.

“There is little interest in infectious diseases in Japanese medical research,” says Dr Ohmagari, who is also Head of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Prevention, Preparedness and Response to Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“I have been an independent infectious disease physician for 18 years now. During this time, however, infectious disease research has been at a low ebb. The development of new drugs has gradually declined in activity.”

Dr Ohmagari confirms that the ageing population’s health is taking priority: “There is a high level of interest in regenerative medicine, genome medicine, cardiovascular disease, which has a large number of patients, lipid disorders and diabetes mellitus.”

Among the indicators of low research activity in the field, Dr Ohmagari points to a lack of collaboration between Japanese infectious disease researchers and colleagues internationally.

“I have the impression that there are not many researchers actively collaborating with foreign countries, perhaps because there are not many researchers in infectious diseases to begin with. Personally, I am conducting research in Vietnam, and I have exchanges and joint clinical trials with researchers in Europe and the United States,” he says.

Professor Masanori Fukushima raises a further issue: the pandemic could have enabled Japanese researchers to better understand the impact on patients, but due to a lack of access to patients at research hospitals this hasn’t been possible on a large scale.

“COVID-19 patients are not concentrated in university hospitals with research capabilities, and the annual number of COVID-19 patients at university hospitals itself is small,” says Professor Fukushima, Representative Director of the Learning Health Society Institute (LHSI) and Professor Emeritus at Kyoto University.

“Patients admitted to university hospitals are referred from other hospitals, seriously ill, and typically emergency cases, making it difficult for university hospitals to establish a system for continuous research on them.

“COVID-19 patients admitted to university hospitals are not treated by specialists in infectious diseases but by specialists in respiratory medicine and cardiology, as respiratory management is the primary treatment for these patients. In addition, hematologists will be in charge of treating patients with thrombosis; COVID-19 is out of the scope of the study due to their expertise (respiratory medicine, cardiology, and hematology).”

Professor Fukushima says that according to the Ministry for Health and Welfare’s policy, patient samples and other data have been concentrated at the NIID, which is under the direct control of the Ministry. “This makes it difficult for university hospitals with research capabilities to plan and develop virological studies,” he says.

He also says that expert advice has also not always been followed. In spring 2021, Professor Fukushima published a paper (Asking about measures to combat the novel coronavirus – Clinical recommendations: COVID-19 control – Critical appraisal and proposals; Rinsho Hyoka (Clinical Evaluation), May 2021) in which he proposed that all strategic and practical measures against COVID-19 in Japan be left to medical associations and university hospitals, and that specialized hospitals be created or designated and patients concentrated there. “Together with Dr Yokokura, the former president of the Japan Medical Association, I submitted the report to the government, the heads of local governments, and the media, but there has been little response so far,” he says.

“Japan used to be at the forefront of vaccination”

Despite these concerns about the lack of support for infectious diseases research, some scientists are quick to point out that Japan has fared relatively well during the pandemic compared with many nations, and in some ways has handled it better.

Professor Suematsu says: “Despite the size of the limited budget, researchers have very actively investigated infectious diseases. Data sharing has been good with COVID, but it should have been much better with infectious diseases.”

One leading researcher who was actively involved in the effort to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in Japan is Professor Hiroaki Kitano, President & CEO of Sony Computer Science Laboratories, Inc. and Professor at Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate School (OIST), who was contacted by the Japanese government to work with the Office for Promotion of Countermeasures against Novel Coronavirus Infections.

Professor Kitano assembled a team of researchers including Dr Makoto Tsubokura of RIKEN who carried out a series of hi-tech simulations to better understand and predict the impact of the contagion on Japanese people within real-world environments, including some important work on the spread of the virus in indoor environments, such as restaurants and bars, and on trains. He has also been involved in international collaborations to produce a global “COVID-19 Disease Map”. See below: Research critical to Japan’s success.

But even Professor Kitano says Japan’s lack of infectious diseases research had impacted on the country’s ability to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. “We’ve failed to create any effective vaccine so far,” he says. “We haven’t got a domestically developed vaccine approved yet – even now.

“Japan used to be at the forefront of vaccination; we had a very strong vaccination program, and very strong companies that would create vaccinations. Many companies have actually withdrawn from the vaccine business, so that has substantially reduced the capability for manufacturing and quick response. At the same time, the research funding for infectious diseases has not been that abundant.”

Perhaps recognizing that it had been slow to develop its own vaccines and needing to catch up, the Japanese government recently pledged US$2 billion for vaccine research against future epidemics.

Professor Kitano’s assessment was that it could take up to three years before Japan has its own approved and manufactured COVID-19 vaccine. On that front, he says: “The game is pretty much over, unless vaccines desired for the next stage of infection control – such as nasal vaccines potentially more effective for infection prevention – are to be developed.”

Nevertheless, Professor Kitano praised the Japanese government for its handling of vaccine contracts with the major pharmaceutical companies, and for its leadership in appointing Mr Taro Kono as a Minister in charge of vaccinations. “I think the end result is that their actions saved many people’s lives – I’m sure of that,” he says.

Japan falls behind – what the data shows

In early 2022, data from Nature Index and Dimensions started to point to a disparity in Japan’s reputation as one of the world’s leaders in research, with the amount of research focusing on infectious diseases surprisingly low compared to other leading nations. Furthermore, it was dramatically lower in the case of COVID-19.

But Japan itself is highly regarded for its research, so how did this occur?

Stung by criticism of the lack of research funds by high-profile researchers such as 2012 Nobel Prize winner Shinya Yamanaka – and perhaps cognisant of league tables that show Japan slipping behind arch-rivals South Korea and China in publications – the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) announced a major overhaul of research funding in 2017, followed up in 2020 with the establishment of a ¥4.5 trillion (US$43 billion) fund for research. However, researchers such as Yamanaka have pointed out that funding allocation can be mixed, with some areas losing out over other hot topics.

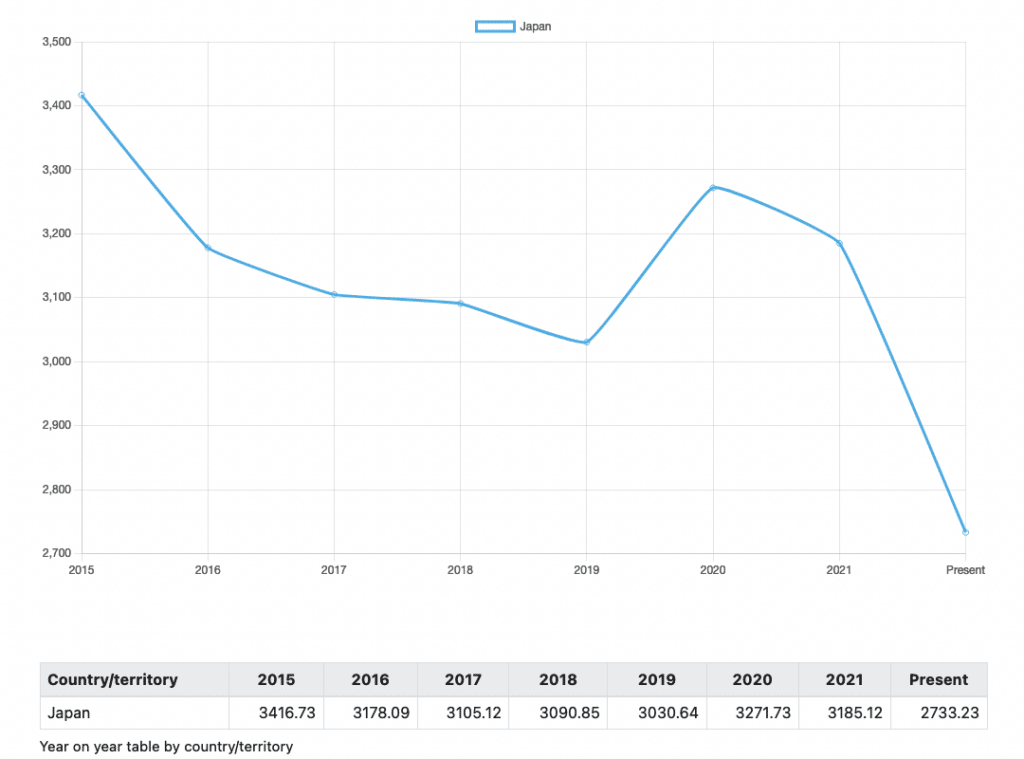

When we look at how these factors play out on the world stage, we can see in data from Nature Index that Japan’s overall research output had been in steady decline from 2015-2019. It saw a rise in 2020 but resumed its decline in 2021 and into 2022. (see Figure 1).

Data derived from Dimensions shows that while Japan ranked fifth in the world in terms of all article outputs in 2019-2021 (see Figure 2), it was ranked below 11th globally for infectious diseases articles (Figure 3).

All research articles in Dimensions (2019-2021)

| United States | 2,357,592 |

| China | 2,141,367 |

| United Kingdom | 729,785 |

| Germany | 612,787 |

| Japan | 568,577 |

| India | 565,016 |

| Italy | 402,965 |

| Russia | 400,272 |

| Canada | 388,198 |

| France | 383,458 |

All infectious diseases publications* in Dimensions (2019-2021)

| United States | 179,465 |

| China | 74,010 |

| United Kingdom | 61,122 |

| India | 42,280 |

| Italy | 33,113 |

| Germany | 26,830 |

| Brazil | 26,053 |

| Canada | 25,252 |

| France | 24,312 |

| Spain | 23,013 |

| Australia | 22,557 |

| Japan | 18,737 |

* includes articles, preprints and conference proceedings.

To put Japan’s research output across all areas in context, between the years 2015 and 2021 Japan accounted for 3.8% of total publications with nearly 1.3 million according to Dimensions data, making it the fifth biggest in the world in terms of output. However, while this position rises to fourth when it comes to cancer research with 5.5% of publications, it drops markedly to below 11th for infectious disease research, accounting for only 2.5%, and this drops to 2% when we look at just the last two years in 2020 and 2021 (see Figure 4).

Japan 2015-2021 – publications* and rank

| Field | Japan Publications | Global Total | % of Global | Rank |

| All fields | 1,279,452 | 34,108,770 | 3.8 | 5th |

| Cancer | 105,924 | 1,926,313 | 5.5 | 4th |

| Infectious Disease | 31,613 | 1,268,300 | 2.5 | <11th |

| Infectious Diseases (2020-21 only) | 15,206 | 745,496 | 2.0 | <11th |

* includes articles, preprints and conference proceedings.

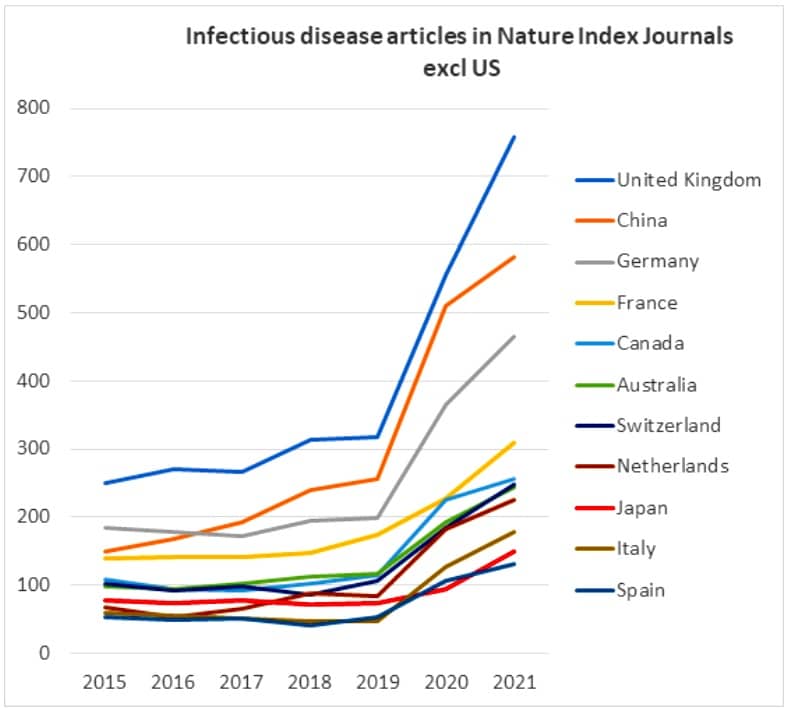

When we flesh this out with the performance of other countries in related areas, we can see that while China, the UK and Germany have surged ahead in recent years when it comes the output of research across 90 different infectious diseases in Nature Index (tracked in Dimensions), Japan has fallen behind the likes of Switzerland and The Netherlands. Even more starkly, it has failed to match the huge spikes in coronavirus-related research seen in other major industrialized countries (in Figure 5, the US has been removed due to it being so far ahead).

The search strings used to draw out infectious disease articles from Nature Index journals in Dimensions were based on those used in the 2021 Nature Index supplement on infectious disease: https://www.nature.com/nature-index/supplements/nature-index-2021-infectious-disease/tables/dimensions-search-strings

As stated earlier, while much of the Japanese government’s funding for infectious diseases research is directed to the National Institute of Infectious Disease (NIID), and despite being regarded as one of the top institutions in Japan for infectious diseases by Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), NIID does not even appear in the top 10 of Japanese institutions by number of publications on COVID in 2020 and 2021, with only 287 articles out of a total of 14,960 articles for Japan – or only 1.9% of the country’s output – while the University of Tokyo had 1,417 articles or 10% of overall publications.

Patents pending?

Further to the earlier criticism about Japan’s reduced vaccine development capacity, by exploring data of patents recorded during the first two calendar years of the pandemic we can see that Japan’s activity has mirrored that of its research performance, ranking 11th in the total number of COVID-19 patents recorded. The countries and regions ahead of it, however, are quite different, with South Korea, India and Taiwan all well ahead of Japan (see Figure 6).

COVID-19 patents recorded in Dimensions (2020-2021)

| United States | 7,254 |

| China | 4,326 |

| South Korea | 1,883 |

| India | 1,600 |

| Germany | 804 |

| Spain | 524 |

| United Kingdom | 521 |

| Taiwan | 421 |

| Canada | 403 |

| France | 359 |

| Japan | 346 |

“We must prepare for the next pandemic.”

While COVID-19 isn’t showing any signs of going away, what lessons can Japan learn from its experience? And what does the future hold for its infectious diseases research and collaborations?

The recent announcement of a concerted vaccination research program to protect against future epidemics in Japan will see a US$2 billion injection of funds into this critical area, which is no doubt welcome news. And while the experts say there needs to be increased government funding for research, that’s not their sole focus.

Dr Ohmagari says despite the lack of infectious diseases research being conducted in Japan, the country already has a good base to build upon. “I think the level of Japanese research on infectious diseases, especially basic research, is high by global standards. However, epidemiological and clinical research is not so active. The number of researchers is small,” he says.

The pandemic might already be spurring on that change: “In recent years, young researchers have gradually become interested in clinical and research work on infectious diseases. I hope that they will quickly build up their strength and produce results.”

Professor Suematsu says Japan must learn from the research and healthcare systems in place in other countries. In particular, he’s “very impressed” with the UK’s approach to foster researchers with integrated biotechnology training, something he says “has never happened in Japan”. He also envies the UK government’s central information overview and a network of data sharing.

Professor Kitano agrees that improved data sharing needs to be an outcome from the pandemic. He also proposes that the government pool all of its experts and learn from their collective experience, “in case the next thing comes”.

“That structure is yet to be seen but I am proposing that we need to have this – a group of people who have gone through this kind of ‘wartime emergency’ and understand how chaotic things can be.”

He says this group would be “more of a permanent structure, to provide the government with expert advice next time we have a pandemic”.

“There is a stronger awareness that Japan may need to do better on this front for the benefit of the population,” he says.

Dr Ohmagari says Japan needs to be ready now for what’s next. “COVID-19 has revealed that there is room for improvement in research and development in the field of infectious diseases in Japan. We must prepare for the next pandemic,” he says.

“We have already started to build a system in terms of policy in Japan. However, the same problem was pointed out after the 2009 pandemic influenza, but no measures had been taken. We must reflect on this. We must continue to promote these policies without interruption.

“This will require political will backed by a deep understanding of the public. And our generation of researchers must do our best to ensure that this trend will never be halted,” he says.

In the words of the late Dr Nakajima, Japan must learn the lessons of its past or risk “fatal complacency”.

“King of masks” – a culture of survival

In his book How to Prevent the Next Pandemic, Bill Gates suggests some harsh lessons the world should learn from its collective experience of COVID-19. Gates had famously published a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2015 expressing concern a worldwide pandemic could cost millions of lives and trillions of dollars. While Gates is critical of much of what happened before and during the pandemic, he reserves praise for some countries’ handling of the chaos. In particular he singles out Japan, referring to the country as the “King of masks”. Japan’s cultural differences have been its salvation.

In 2022, the world has, for the most part, tried to move on from the COVID-19 pandemic. In many countries, to walk around the streets of busy cities now, one would hardly notice that something so monumental had happened. One or two people wearing masks and some faded signs on shop windows pointing out abandoned policies for customers are all that is left of those days not so long ago when towns and cities were under lockdown.

In Japan, however, things are different. While restrictions are easing, many rules are still in effect, and mask-wearing is ubiquitous. Measures such as plastic panels between diners in restaurants and donning of plastic gloves when collecting food at buffets still persist in Tokyo and other major cities – measures that were ditched long ago in other countries, if they were ever adopted in the first place. Japan and its strict procedures have received more coverage than most in the global media, thanks in part to its relatively good record on COVID-19, but also because it hosted the single biggest global event of 2021 in the shape of the Tokyo Olympics, delayed from 2020 at the height of the pandemic, and held with hardly any spectators from outside Japan. The resolute approach to put on the Games no matter what and the mandate of strict adherence to social distancing and other measures meant that Japan was put under a huge amount of scrutiny in the Western media, intrigued about how the country and its government approached the event.

When it came to a critical test, the stereotypical image of Japan as an ordered, disciplined population, one that is prepared to comply with restrictions, has worked in its favour. Like many countries, Japan has also seen protests and political backlash. And like many, Japan has also been hit with additional waves of infections, continuing to test its resolve.

Research critical to Japan’s success

Despite criticism of a lack of research into infectious diseases and COVID-19 in Japan, the country also saw some outstanding examples of scientific and technological knowhow, helping to safeguard the community.

Professor Hiroaki Kitano, President and CEO of Sony Computer Science Laboratories Inc., played a central role in the early days of the pandemic to better understand the spread of the virus and how it could be protected against.

Professor Kitano was able to use the modelling his teams had produced to show the startling impact preventative measures had on the spread of the disease. In two areas – confined spaces, such as a karaoke bar (see image and video), and mask-wearing – Professor Kitano was able to show the efficacy of certain restrictions that could massively reduce infection of COVID-19 and its variants. This helped to justify lockdown procedures but also supported a measured opening up of society with certain behavioural guidelines, such as maintaining contact within your own community – known as the “Stay with your community” campaign in late 2021.

He also demonstrated an optimal vaccination strategy that was implemented during late spring to fall of 2021 possibly resulted in very low COVID-19 cases in Japan in the fall of 2021.

The ability of Professor Kitano and his colleagues in Japan in translating the data they had collected and impacting policy may have been crucial in keeping the number of deaths so low since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic; even more remarkable in an environment in which the country has faced declining levels of funding and publications in infectious disease research.

About Dimensions

Part of Digital Science, Dimensions is a modern, innovative, linked research data infrastructure and tool, re-imagining discovery and access to research: grants, publications, citations, clinical trials, patents and policy documents in one place. www.dimensions.ai

About Nature Index

The Nature Index is a database of author affiliations and institutional relationships. The index tracks contributions to research articles published in 82 high-quality natural-science journals, chosen by an independent group of researchers.

The Nature Index provides absolute and fractional counts of article publication at the institutional and national level and, as such, is an indicator of global high-quality research output and collaboration. Data in the Nature Index are updated regularly, with the most recent 12 months made available under a Creative Commons licence at natureindex.com. The database is compiled by Nature Portfolio, part of Springer Nature.

Image credits:

Main image: Masked commuters in Osaka, Japan. Source: Stock image.

Face masks on sale in Japan. Source: David Swinbanks.

Glove dispensers in a Japanese restaurant. Source: David Swinbanks.

Masked geisha dolls. Source: Rafael Randy Cardoso Garcia.

COVID-19 test and Tokyo 2020 Games concept. Source: Stock image.

Masked commuters in Tokyo, Japan. Source: Stock image.

Simon has 20 years’ experience in scholarly communications. He has lectured and published on the topics of bibliometrics, publication ethics and research impact, and has recently authored a book on predatory publishing. Simon is also a COPE Trustee and ALPSP tutor, and holds Masters degrees in Philosophy and International Business. He lived and worked in Japan for three years in the 1990s.

David has 30 years’ experience in media and communications. With a background in broadcast journalism, his career focus has been in research communication – including science, health science and medicine – spanning 25 years of service in the university sector. His experience also includes both internal and external communications in the health and manufacturing sectors.

David is Chairman for Springer Nature in Australia and New Zealand and Founder of Nature Index. He is also a Senior Advisor to Digital Science. Following a postdoc in deep-sea research at Tokyo University, David began his career with Nature as Tokyo Correspondent in 1986 and established Nature Japan KK in 1987 with two Japanese colleagues, which expanded to 120 employees by 2012 spanning the Asia-Pacific region.

The post Pandemic exposes critical gaps in Japan’s health research appeared first on Digital Science.

from Digital Science https://ift.tt/s4R21eD

No comments:

Post a Comment