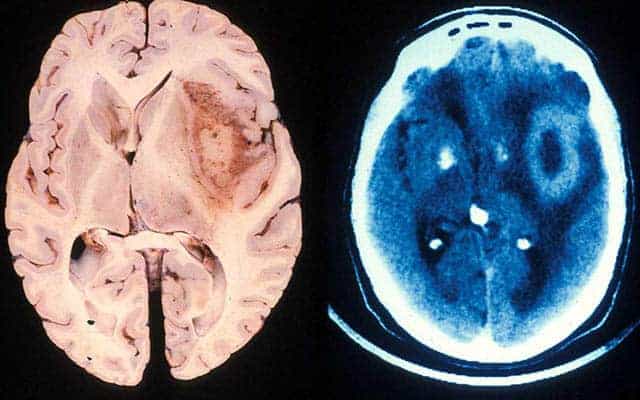

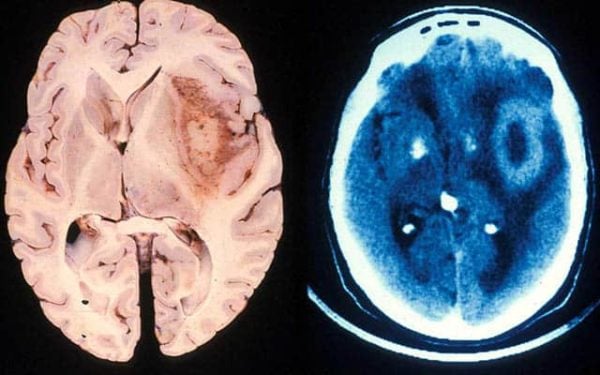

Northwestern Medicine scientists have discovered a new biomarker to identify which patients with brain tumors called glioblastomas — the most common and malignant of primary brain tumors — might benefit from immunotherapy.

The treatment could extend survival for an estimated 20% to 30% of patients. Currently, patients with glioblastoma do not receive this life-prolonging treatment because it has not been fully understood which of them could benefit.

“This is an important breakthrough for patients who have not had an effective treatment in the cancer drug arsenal available to them,” said Dr. Adam Sonabend, the senior/corresponding author of this study, and associate professor of neurosurgery at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a Northwestern Medicine brain-tumor neurosurgeon. “It might ultimately influence the decision on how to treat glioblastoma patients and which patients should get these drugs to prolong their survival.”

“Our study emphasizes important immune cells that might be relevant for response to immunotherapy. We hope that ultimately this benefits glioblastoma patients,” said Victor Arrieta, a post-doctoral scientist at the Sonabend lab and the first author of this study.

The immunotherapy response marker now needs to be validated in a clinical trial to make sure the study findings are reproducible and applicable to any glioblastoma patient, Sonabend said. He also is a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

Glioblastomas are the most common form of malignant brain tumors in adults and have the worst prognosis. Patients are treated with radiation and chemotherapy, but the cancer inevitably recurs. Upon recurrence, there are no treatments that prolong survival.

But Sonabend and his research team’s biomarker discovery shows which patients will respond to immunotherapy and could have their lives significantly prolonged. The finding was confirmed in two independent sets of patients. The new study describes a simple analysis that was able to differentiate the tumors from the patients who responded and lived longer after getting these drugs.

The higher the amount of the biomarker a patient had in their tumor, the greater their chance of extended survival with the drug.

How does the immunotherapy work?

Cancer cells have learned how to activate the brake on the immune system to prevent it from attacking the cells, giving them free rein to replicate.

“This immunotherapy that releases the immune system’s brake and thwarts the cancer cells has been the most important breakthrough for many cancers in the last 20 years,” Sonabend said. “Now, we can potentially use it for glioblastomas.”

The immunotherapy is called PD1 immune checkpoint blockade. PD1 is a protein found on T cells (a type of immune cell) that helps keep the body’s immune responses in check. When this protein is blocked, the brakes on the immune system are released and the ability of T cells is unleashed to kill cancer cells.

The biomarker the Sonabend group identified is phosphorylated ERK, meaning it has a phosphate group bonded to it. It’s the final protein on one of the biochemical cascades that signals the cancer cells to start proliferating. When there’s a lot of phosphorylated ERK, the immunotherapy is most effective, the study showed.

Why scientists previously thought the immunotherapy didn’t work

Several clinical trials involving hundreds of glioblastoma patients have tested the immunotherapy (PD1 immune checkpoint blockade.) These studies failed to show an overall extension of survival for glioblastoma when comparing all patients who got this treatment versus those who did not. Thus, these studies have been interpreted as having negative results. Yet, on these studies a subset of patients appears to show a robust response and long-term survival.

This is the subset of patients that Sonabend’s group studied to discover why they responded.

“We tried to see if there was something different about these tumors that indicated some patients would live longer when getting this immunotherapy,” Sonabend said.

They discovered a way to identify which patients with malignant brain tumors called glioblastomas might be the ones who benefit from immunotherapy.

Research notes

The study was published Nov. 29 in Nature Cancer.

Other Northwestern authors are Víctor A. Arrieta, Seong Jae Kang, Crismita Dmello, Kirsten B. Burdett, Catalina Lee-Chang, Joseph Shilati, Dinesh Jaishankar, Li Chen, Andrew Gould, Daniel Zhang, Christina Amidei, Rimas V. Lukas, Jonathan T. Yamaguchi, Matthew McCord, Daniel J. Brat, Hui Zhang, Lee A. D. Cooper, Bin Zhang, Roger Stupp, Amy B. Heimberger and Craig Horbinski.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) grant 1R01NS110703-01A1, NIH Office of the Director grant 5DP5OD021356-05 and NIH/National Cancer Institute grant P50CA221747 SPORE for Translational Approaches to Brain Cancer.

from ScienceBlog.com https://ift.tt/3I76g37

No comments:

Post a Comment