When testing hypotheses on how horses synchronize their herd behavior, computational modeling is a must. So much more is happening among the many mares, stallions, and foals that simple math equations cannot fathom.

“Much like human societies, horses have a much more complex society than most birds or fish, for which there are many successful studies in making behavioral models,” explains research leader Tamao Maeda.

In the social structure of feral horses, small stable unit groups aggregate into a larger social organization called a “herd”. This is analogous to human families gathering to form a local community, which further combine to form higher social units from cities to countries.

The problem is the animal’s virtual size, both in terms of its group population and the vastness of their distribution. The relative scarcity in their behavioral synchronization studies may be due to such challenges in observing the macroscopic structure of feral horses.

The joint team from Strasbourg University and Kyoto University solved that problem with the use of drones to observe the spatial structure and herd behavior of a hundred feral horses simultaneously in Serra D’Arga, Portugal.

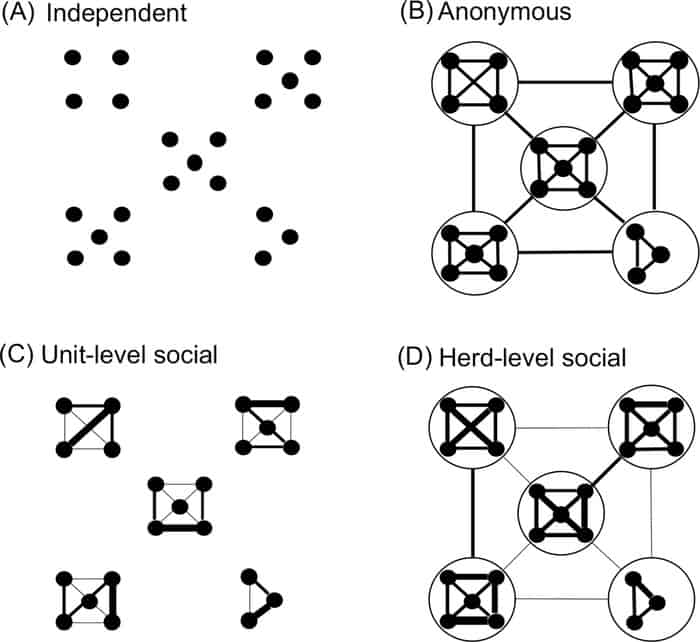

Maeda’s team used a multi-agent computerized system (MAS) for their research, which is appropriate for target surveillance and social structure modeling. In their MAS, they applied different hypothetical rules: First, are individuals independent? So, a foal would not count.

Second, do individuals randomly synchronize their behavior? Or is there a possible pattern of selection?

Third, and a more intriguing question is, do individuals synchronize according to their social network? To test this hypothesis, two sub-models were created, one of which only takes into an account the same unit group members, such as in a human clique. The other sub-model applies to the entire herd.

The simulation and empirical data clearly support the last hypothesis, suggesting that the feral horses coordinate with other individuals not only within a unit group but also at an inter-unit-group level. Surprisingly, inter-individual interactions occur among spatially-separated horses as well.

This behavior contrasts with most previous studies that have suggested that socially complex animals synchronize the behavior of only a few nearby individuals and that such local interactions then create the global synchronization.

Among the feral horses, however, the average nearest unit distance was 39.3m while the nearest individual within the same unit was 3.2m. Maeda’s results suggest that the horses developed an ability to recognize the behavior of even those individuals that were spatially very distant from them.

The joint research team are encouraged by this effective use of drones and a model with simple rules integrating social relationships in simulating the behavioral synchronization of animals living in one of the most complex societies known.

Research leader Shinya Yamamoto concludes, “As our model is applicable to other animal groups, this study on collective synchronization will contribute to an understanding of the evolution and functional significance of complex animal societies.”

The paper “Asymmetric Total Synthesis of Shagenes A and B” appeared on https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0258944

from ScienceBlog.com https://ift.tt/2ZveJvP

No comments:

Post a Comment