Describing a previously unknown genetic condition that affects children, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine and Rady Children’s Institute for Genomic Medicine say they also found a potential method to prevent the gene mutation by administering a drug during pregnancy.

The findings publish in the September 30, 2021 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine.

The work involved researchers in Egypt, India, the United Arab Emirates, Brazil and the United States. “Although different doctors were caring for these children, all of the children showed the same symptoms and all had DNA mutations in the same gene,” said senior author Joseph G. Gleeson, MD, Rady Professor of Neuroscience at UC San Diego School of Medicine and director of neuroscience at the Rady Children’s Institute for Genomic Medicine.

The research team dubbed the condition “Zaki syndrome” after co-author Maha S. Zaki, MD, PhD, of the National Research Center in Cairo, Egypt, who first spotted the condition. Zaki syndrome affects prenatal development of several organs of the body, including eyes, brain, hands, kidneys and heart. Children suffer from lifelong disabilities. The condition appears to be rare, but future studies are required to determine prevalence.

“We have been perplexed by children with this condition for many years,” said Gleeson. “We had observed children around the world with DNA mutations in the Wnt-less (WLS) gene, but did not recognize that they all had the same disease until doctors compared clinical notes. We realized we were dealing with a new syndrome that can be recognized by clinicians, and potentially prevented.”

Co-author Bruno Reversade, PhD, a research director at the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in Singapore, helped identify several families with members suffering from Zaki syndrome and investigate potential therapeutic intervention.

“While we have shown that it’s possible to mimic WNT-deficiency with dedicated drugs, the real challenge was to overcome, and possibly rescue, this congenital disease,” Reversade said.

Using whole genome sequencing, researchers documented mutations in the WLS gene, which controls signaling levels for a hormone-like protein known as Wnt (pronounced wint). Wnt signaling is a highly conserved group of protein pathways involved in embryonic development.

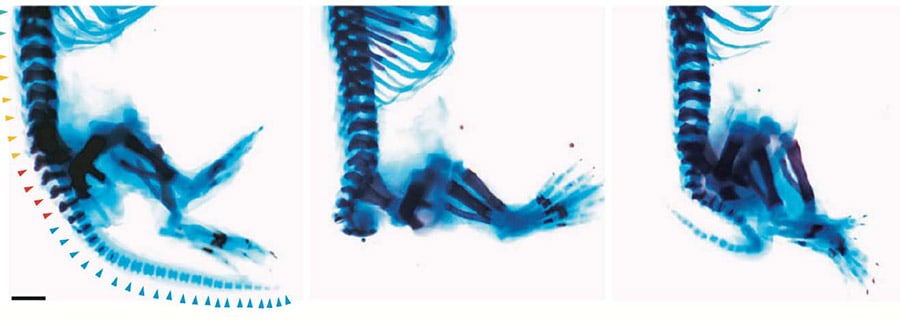

The scientists generated stem cells and mouse models for Zaki syndrome, and treated the condition with a drug called CHIR99021, which boosts Wnt signaling. In each mouse model, they found CHIR99021 boosted Wnt signals, and restored development. Mouse embryos grew body parts that had been missing and organs resumed normal growth.

“The results were very surprising because it was assumed that structural birth defects like Zaki syndrome could not be prevented with a drug,” said first author Guoliang Chai, PhD, a former postdoctoral fellow at UC San Diego School of Medicine now at Capital Medical University in Beijing, China. “We can see this drug, or drugs like it, eventually being used to prevent birth defects, if the babies can be diagnosed early enough.”

Co-authors include: Changuk Chung, Zhen Li, Lu Wang, Trevor Marshall, Nan Jiang, Xiaoxu Yang, Jennifer McEvoy-Venneri, Valentina Stanley, Paula Anzenberg and Nhi Lang, all at Rady Children’s and UC San Diego; Karl Willert, UC San Diego; Emmanuelle Szenker-Ravi, Muznah Khatoo and Vanessa Wazny, Genome Institute of Singapore; Jia Yu and David M. Virshup, National University of Sinapore; Rie Nygaard, Filippo Mancia, Rebecca Hernan and Wendy K. Chung, Columbia University; Rijad Merdzanic and Aida M. Bertoli-Avella, Centogene, Germany; Maria B.P. Toralles and Paula M.L. Pitanga, Laboratorio e Genetica Medica, Brazil; Ratna D. Puri, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital; and Nouriya Al-Sannaa, Dhahran Health Center, Saudi Arabia.

Funding for this research came, in part, from the National Institutes of Health (R01NS048453 and R01NS09800), the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (51486313), the Yale Center for Mendelian Disorders (U54HG006504), the Broad Institute Center for Mendelian Genomics (UM1HG008900), the Center for Inherited Disease Research (N01 268201700006I-0-26800029), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Rady Children’s Institute for Genomic Medicine, a National Medical Research Council Open Fund–Young Individual Research Grant, the National Research Foundation (Singapore), the Branco Weiss Foundation (Switzerland), the European Molecular Biology Organization Young Investigator program, the Strategic Positioning Fund for Genetic Orphan Diseases, and an inaugural A*STAR Investigatorship from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research in Singapore.

from ScienceBlog.com https://ift.tt/3m5YNak

No comments:

Post a Comment